The past. The present. The future. These are all terms used to help describe time. They are relative references; relative to the now. The past occurs before the now; the present occurs simultaneously with the now; the future occurs after the now. But what is the now?

Now is a term I use to describe the temporal location when I am. It is hard to describe exactly, except to say that I am always in the now. As soon as I remember something, that something is already in the past, having occurred before the now. The future often includes those events I want to eventually occur in the now. When I consider my conscious self—what I often referred to as “I”—that conscious self always exists in the now. I cannot exist consciously in the past or in the future. Remembering the past is not existing in the past, just as expectation of the future is not existing in the future. My conscious self is always existing in the now. My conscious self is a reference point I can use; a reference to the now.

Thinking in this way, I quickly notice that time is always relative to me, specifically to my conscious self. Every event occurs either before, simultaneously with, or after the now. Can I quantify these terms any further, that is, can I suggest that there is a long before and a shortly before? Saying long before seems to suggest a quantifiably large value of time, just as shortly before seems to suggest a quantifiably small value of time. However, as I will demonstrate, really all that is occurring is a larger or smaller number of other events between the now and the event that occurred either long before or shortly before.

Consider how we determine time. While I write this post, it is Sunday, May 24, 2020 at about 10:48 am. This is a very specific reference I am making, though I could be even more specific had I chosen. But what precisely does it mean? Sunday is a description of the “day of the week,” often considered the first day of a seven day sequence of days. The selection of the “first day” of a sequence of seven days is fairly arbitrary. May is the month, made up of thirty-one days, and is also considered approximately one twelfth of a year. The 24 is a reference to the twenty-fourth day of the month being considered. The 2020 is the year, counted from an arbitrary point in the past. The two terms that need further explanation are day and year, as both seem to tell us a great deal about the particularity of the values in this description.

So what is a day? It is suggested by most that a day is one full revolution of the Earth about its axis (given that the Earth’s axis is tilted approximately 23.5 degrees, though that value changes over time). If we assume this is the case, then when the Earth rotates a full 360 degrees, a day has occurred. It is suggested that a year is one full orbit of the Earth around the Sun. If we assume this is the case, then when the Earth completes a full orbit of 360 degrees around the Sun, a year has occurred. However, in both cases, the rotation and orbit of the Earth are inconsistent. That is, the rotational speed of the Earth fluctuates as does the speed at which the Earth orbits the Sun. Furthermore, the Earth’s orbit is not entirely consistent either, straying from the path it takes slightly upon each circuit. These variances can be accounted for by the influences of other celestial bodies. The Earth is not alone in the void of the cosmos.

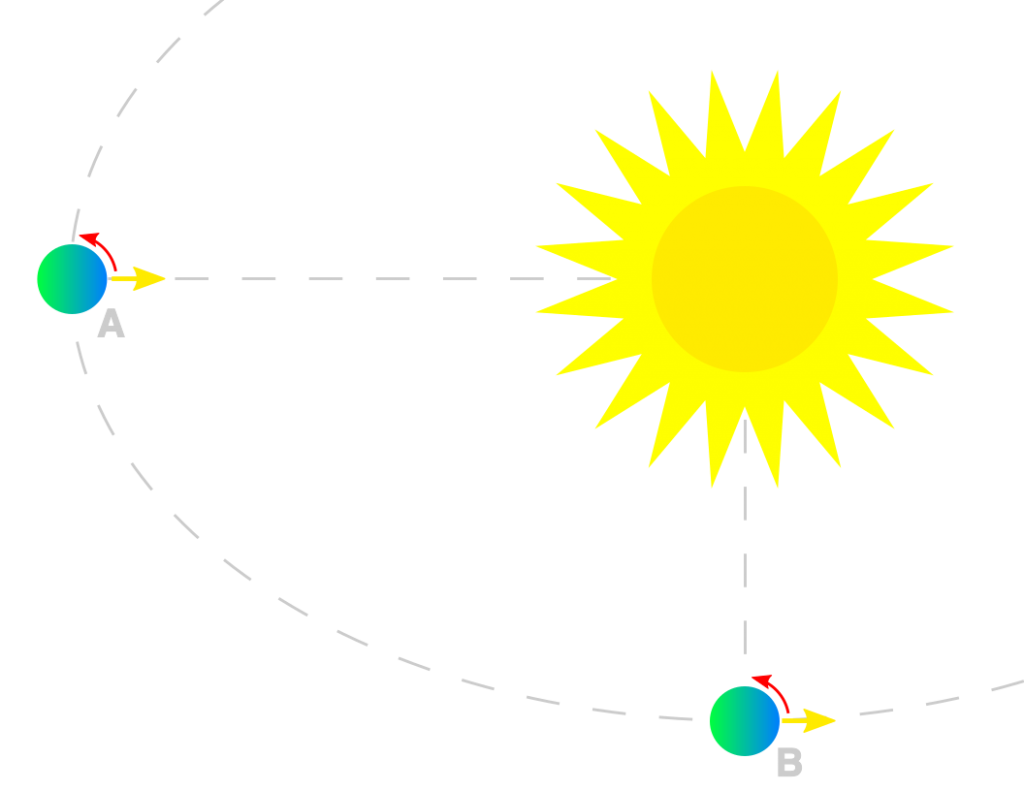

While those variances are generally quite small, to be imperceptible and likely negligible, if I am to determine an accurate account of time, those variances need to be considered. Furthermore, there is reason for me to believe that these values are themselves suspect. Consider the motion of the Earth around the Sun. When the Earth completes one full rotation, it is no longer in the same position it was in at the beginning of its rotation. Both rotation and orbit occur simultaneously. I will use the following diagram to emphasize my point:

When the Earth rotates about its axis, it moves along a trajectory around the Sun. If at one position (A), the direction the Earth faces relative to the Sun is with the arrow pointed at the Sun, at another position (B), the arrow will be pointed perpendicular to the Sun. That is, in each new position the Earth is in after completing a full 360 degree rotation about its axis, the Sun will appear at a different spot in the sky, if I am an observer standing on the Earth (assuming I remain stationary relative to the Earth).

This description of a day does not seem consistent with other ways of describing a day. For example, I have often heard a day described as the time it takes for the Sun to reach the highest point in the sky from when it last was at the highest point in the sky. Following from this description, if I suggest that the Earth will complete approximately 365 full rotations about its axis when it completes approximately one full orbit around the Sun, then a day is actually closer to a 361 degree rotation about its axis, or slightly more than a full rotation.

It is not important here for me to determine with perfect measured accuracy precisely how much of a rotation of the Earth constitutes a day, nor how many days there are in a year. What is important to notice is that all of these time determinations are all relative to events. In particular, not only are they concerned with what comes before, simultaneously, and after, but they are also concerned with counting relatively regular events, such as the number of times the Earth rotates on its axis, or the number of times the Earth completes an orbit around the Sun. The year 2020 is suggesting that since a particular prescribed event had occurred in the past, the Earth had completed 2020 orbits around the Sun. The date of May 24 suggests that since a particular prescribed event had occurred in the past, the Earth had completed 145 approximately full rotations about its axis. In order for me to understand what these descriptions mean, I need to know the particular prescribed events. I need to know that the reference for the year is relative to the occurrence of when Jesus had been born according to the Christians. I need to know that the reference for the day is relative to the arbitrarily decided upon event that is considered the beginning position of the orbit of the Earth around the Sun.

The description of 10:48 am can be described similarly, though instead of counting full occurrences of the Earth’s rotation about its axis, I will need to approximate the fractions of a rotation. For example, to say 10 am is to say that the Earth had completed 5/12 of a full rotation since the particular prescribed event of when the Earth was last facing away from the Sun (relative to my position on the Earth, based on time zone, etc). There are 24 hours in a day, so an hour is one 24th of a rotation. There are 60 minutes in an hour, so a minute is one 1440th of a rotation. There are 60 seconds in a minute, so a second is one 86400th of a rotation.

Therefore, when described in this way, time is simply a description of what is before, simultaneous, and after. In order to introduce some sort of quantifiable measure into the description, a count of regularly occurring events is added to the description. For example, long before will include a larger count of event occurrences than shortly before. This is one manner in which time is often described, however, it is not the only manner. As I’m sure you may already be aware, time on the smaller scale (minutes, seconds, etc) are not usually described by fractions of days, but by counting a different reference event. That will be the subject of my next post.